Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 1

Effect of sustainable agriculture on livelihood diversification strategies of rural communities in Niger State, Nigeria

Sanchi ID1, Alhassan YJ2*, Abubakar A3 and Umar A32Department of General Studies, Federal University Wukari, Taraba State, Nigeria

3Department of Geography, Adamu Augie College of Education Argungu, Kebbi State, Nigeria

Received: 04-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSF-22-52607; Editor assigned: 07-Mar-2022, Pre QC No. AAFSF-22-52607 (PQ); Reviewed: 21-Mar-2022, QC No. AAFSF-22-52607; Revised: 28-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSF-22-52607 (R); Published: 05-Apr-2022, DOI: 10.51268/2736-1799.22.10.72

Abstract

Agricultural sustainability is a necessity in rural areas, where farming alone rarely provides sufficient means of survival. Conceptualization of agricultural sustainability and sustainable livelihood as plurality of activities from past studies is paramount for improved livelihood condition. Twenty percent of villages from each of Kaiji and Shiroro LGAs were drawn. Ten percent of wards in each of the LGAs were selected, from which 2.5% of households were used to give 309 respondents. Data were analyzed using frequency counts, percentage, means and ANOVA. Respondents? age, household size and income were 52.3 ± 10.9 years, 4.82 ± 1.88 and N18851.85 ± 16593.65 respectively. Most (96.3%) of the respondents were males, married (87.9%) and Christians (63.0%). Majority had farming as primary occupation (57.34%), no formal education (62.2%) and acquired their land through inheritance (73%). Most (72.4%) of them diversified into arable crop farming while 57.0% into off-farm activities. Majority (72.4%) diversified for sales and consumption only while 76.3% diversified in both seasons. Rural households had low livelihood assets (x=37.39 ± 11.67) and activities (x=3.15 ± 1.27) while they had high livelihood abilities (x=63.27 ± 12.53). Constraints to livelihood sustainability were lack of infrastructural facilities (91.9%), inadequate livelihood assets (82.0%) and poor transportation system (66.9%). Respondents? level of livelihood sustainability was significantly increased by primary occupation (β=0.64), income from farming (β=0.16), length of stay (β=0.28) and income from non-farm activities (β=0.13). Significant relationship existed between constraints (r=-0.130) and level of livelihood diversification. However, frequency of visits to urban centres (β=-0.25) significantly reduced respondents? level of livelihood sustainability. Livelihood assets (F=35.095), activities (F=2.891) and level of livelihood sustainability (F=6.075) were also significantly different across the two LGAs. Livelihood sustainability was significantly influenced by livelihood ability (β=0.860), assets (β=0.29) and activities (β=0.09) among rural households across the LGAs. Level of livelihood sustainability of rural households was low, in spite of their high level of livelihood abilities. Therefore, enhanced livelihood and agricultural extension in rural development initiative could improve livelihood sustainability of rural households in Niger State.

Keywords

Sustainable livelihood, Diversification, Livestock, Rural households.

Introduction

The term agriculture tends to be associated with sustainable livelihood and rural development. No matter what the name of the system, approach or programme. The major function of agriculture remains that of food security (Abdulai A and CroleRees A, 2001). At the same time, agriculture is an organizational instrument utilized to facilitate sustainable livelihood development. Its purposes may differ, from technology transfer to problem- solving educational approaches to participatory programmes aimed at promoting food security, provision of employment, livelihood sustainability, alleviating poverty and advancing community involvement in the process of development. Internationally, extension's institutional systems tend to enhanced improved food access, availability and utilization (Adekola G and Olajide OE, 2007).

A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (including both material and social resources) and activities required for a means of living. A livelihood is sustainable when it can cope with and recover from stresses and shocks and maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets both now and in the future, while not undermining the natural resource base” (DFID 1999). The underlining principle in the sustainable livelihoods concept involves the identification of assets and resources available or accessible to rural people. These assets, according to (Davies S, 1996) constitute a stock of capital which can be stored, accumulated,exchanged, transformed into use-values and reproduced to counter the negative effects of the trends, shocks and seasonal changes on livelihoods and can be analyzed at individual, household and communities levels. It proposes that for livelihoods to be sustainable, all the social groups represented by these levels of analysis should be able to meet their basic needs (food and income) without compromising the natural resources or environment of their communities. The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach is a means of analyzing and understanding the activities, assets, opportunities and needs of rural people. It describes the various assets, structures, processes and methods that rural people adopt in pursing their livelihoods, as well as the main factors affecting rural people and the inter-relationships between these factors (Adeokun OA et al., 2011).

Livelihood strategies have been classified according to different criteria. (Scones, 1998) divides rural livelihood strategies into three broad types according to the nature of activities undertaken: agricultural intensification, livelihood diversification and migration. These categories, according to Marshland (2002), are not necessarily mutually exclusive and trade-offs between option types and the possibility to combine elements of different options will exist (Davies S and Hossain N 1997).

Methodology

Description of study area (1)

The study was carried out in Shiroro and Kainji Dams. The population of Shiroro is projected in 2020 to be 322,918 people using 3.2% growth rate (NPC, 2006).The climate, edaphic features and hydrology of the state allows sufficient opportunities for harvesting fresh water fish such as Alestes spp, Bagrus spp, Clarias spp, Gymnarchus niloticus etc and permit the cultivation of most of Nigeria's staple crops such as maize, yam, rice, millet and sorghum.

The Shiroro hydropower reservoir is a storage based hydroelectric facility located in Shiroro Local Government, Niger State at the Shiroro Gorge with approximately between Latitude 90° 46' 35 and 100° 08' 36 N and Longitude 60° 50' 51 and 60° 53' 14 N.

It is located approximately 90 km southwest of Kaduna on River Dinya (Aderinto A 2012).

Description of the study area (2)

Kainji Lake is located between longitudes 4°21’ and 4°45’ East and latitudes 9°5’ and 10°55’ North. It cuts across the Niger and Kebbi states, and is mostly located in Niger state (De Janvry 1981). Kainji is the second largest lake and the largest man-made lake in Nigeria (Umar and Illo 2014). It was created in 1968 following the impoundment of the Niger River by the construction of the Kainji Dam at New Bussa, in Borgu Local Government Area of Niger State (Dercon S and Krishnan P 1996). It has a maximum length of 134 km, a maximum width of 24.1 km, a mean and maximum depth of 11 m and 60 m, respectively, a surface area of 1,270 sq. km, a volume of 13 × 109 m3, and a catchment area of 1.6 × 106 sq. km (Obot 1989). The climate of the Kainji Lake usually alternates between dry and rainy conditions. The total annual rainfall for the Lake ranges between 1,100 mm and 1,250 mm, spreading from April to October.The highest amount of rainfall is observed in August. The highest (about 30°C) and the lowest (about 25°C) monthly temperatures are recorded in March and August, respectively (Babulo B et al., 2008).

Method of data collection

Both primary and secondary data were collected for the study. Primary data was obtained with the aid of structured interview and structured questionnaire designed in line with the study objectives. The copies of which were administered to the respondents selected for the study (Devereux S 1993). Data collected included information on the socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents, level of livelihood activities etc. Secondary data was sourced from relevant text books, journals, seminar documents, conference articles, annual reports and other relevant materials (Bakar TT, 1999).

Sampling procedure and sample size

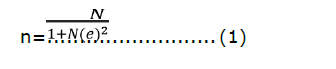

The study employed multi-stage sampling technique to collect the data. Firstly, two LGAs in Niger State was Purposively Selected (Davis JR and Bezemer D 2003). The LGAs are Shiroro and Kainji. Secondly, 20 Villages from each of the two LGAs giving a total of 40 villages. Thirdly, eight 10 farmers were drawn at random from each of the selected villages, thus making 200 farmers in Shiroro and 205 in Kainji making 405 respondents from the two LGAs. Yamane (1973) formula was used to estimate the sample size from the sampling frame in each study location. The formula is given as:

Description:

n=Number of samples required

N=Population number

e=Error Rate sample (sampling error), (Tables 1-6).

Results and Discussion

Age distribution of the respondents, as presented in Table 1 shows that 60.6 percent of the respondents were 55 years old and below while the mean age was 52.3 years. This suggests that majority of the respondents were in their productive age and have vigor to engage in livelihood activities (Daneji MI, 2011). Age is an important factor when considering livelihood activities. This is because education, skills, access to capital assets and policy specificity vary across age groups. It has been argued that age, in some instances, could be an entry criterion for some livelihood activities (C r a i g , 2001). This result is consistent with the reports of Oyesola and Ademola, 2011 who reported that most of the labor forces in rural areas of southwest Nigeria were of ages 20-55 years. This is expected to have positive impact on rural livelihood diversification. (Butler and Mazur 2004) asserted that livelihood diversification is higher in younger rural dwellers when compared with the older ones in Uganda (Devereux S, 1993).

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) Less than 25 |

20 | 4.6 | Mean=52.3 |

| 26-40 | 45 | 11 | SD=0.97 |

| 41-55 | 182 | 45 | |

| 56-70 | 138 | 34.1 | |

| Above 70 | 20 | 4.9 | |

| Sex Male |

390 | 96.3 | |

| Female | 15 | 3.7 | |

| Marital status Single |

9 | 2.2 | |

| Married | 356 | 87.9 | |

| Widowed | 30 | 7.4 | |

| Divorced | 10 | 2.5 | |

| Education No formal education |

252 | 62.2 | |

| Primary education | 96 | 23.7 | |

| Secondary education | 25 | 6.2 | |

| Tertiary education | 9 | 2.2 | |

| Adult education | 13 | 3.2 | |

| Vocational training | 10 | 2.5 | |

| Monthly income in naira ≤ 5,000 5,001 – 10000 |

69 111 |

17 27.4 |

Mean=N18,851.85 SD=16593.65 |

| 10,001 – 20,000 | 82 | 20.2 | |

| 20,001 – 30,000 | 62 | 15.3 | |

| 30,001 – 40,000 | 23 | 5.7 | |

| 40,001 – 50,000 >50,001 |

29 29 |

7.2 7.2 |

The result in Table 1 shows that the majority (96.3%) of respondents were male, while 3.7 percent were female. This implies the dominance of male household heads over the females in the scene of rural income- generating activities. This result is in agreement with the claim of (Ebitigha, 2008) and (Oludipe, 2009) that males still dominate rural income-generating activities (Devereux S, 2001).

The marital status as indicated in Table 1 shows that an overwhelming proportion (87.9%) were married, 2.2% single, 7.4% widowed and 2.1% divorced. The importance of marital status cannot be undermined when studying livelihood because of its influence on access to efficient use of livelihood assets as well as changing roles and responsibilities.

The implication of this result is that the respondents were responsible and mature adults who were likely to show more commitment to their work and wisely use available resources for different livelihood activities in which they are involved. While reiterating the importance of marriage in livelihood study, (Ebitigha, 2008) and (Oludipe, 2009) asserted that marriage can both increase access to livelihood assets, especially among women and thereby increase the level of their activities.

The results in Table 1 also show the distribution of the respondents based on their highest level of education. Analysis of the result reveals that majority (62.2%) had no formal education, 23.8% had primary education, 6.2% had secondary education, 2.2% had tertiary education, 3.2% had adult education, while 2.5% had vocational training.

The result indicates respondents‟ high level of illiteracy. This may significantly increase language barrier in communication with the resultant effect of low understanding and acceptance of policies that can promote accessibility and sustainability of livelihood. Oladeji and Oyesola, 2000 observed that education plays a major role in information communication, as it is necessary for coding and decoding of information in some media.

Table 1 also shows the distribution of the respondents based on their monthly income. Less than half of the respondents 27.4%, 20.2% and 15.3% earned between N5001- N10000,-N10001- N20000 and N20001- N30000 respectively as their monthly income. The mean income was N18851.85 while a few respondents (12.9%) earned between N30001- N50000 per month. This is an indication that the monthly income level of the respondents in the study area is low.

This result is contrary to that of (Babatunde RO and Qaim M, 2009) in similar studies on livelihood diversification. They reported that rural households‟ monthly income was high with mean amount of N65, 000. The result is however consistent with that of who reported a low mean income level of N35, 000 among rural households in Osun state, Nigeria (Dercon S and Krishnan P 1996).

Aggregation of the scores for livelihood abilities in Table 2 reveals that 51.4% of the respondents had high level of livelihood ability while 48.6% had low level of livelihood ability. Ellis, 2000 avers that livelihood ability does not only include sheer physical labor but also knowledge, age, support, skills and years of experience.

| Level of livelihood abilities |

Score range | Frequency | Percentage | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 31.00-63.26 | 197 | 48.6 | 63.27 | 12.5 |

| High | 63.27-103.00 | 208 | 51.4 | ||

This result implies that respondents in the study area have an appreciable level of ability that is expected to increase their livelihood diversification. However, there is still the need for extension support in terms of capacity building in various aspects of livelihood respondents may engage and provision for educational opportunities, especially formal education for increase in knowledge and development of entrepreneurship skills.

Table 3 highlights the various activities engaged in by the respondents. The activity and the percentage involved in each activity were presented in this table.

| Livelihoods category | Livelihood activities | Frequency* | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Own farm | Arable farming Tree Cashew Fish farming |

342 19 121 |

84.4 4.7 29.9 9.9 |

| Off-farm/processing activities | Cassava processing Oil Hunting Milling of farm products Grinding of pepper |

177 23 27 45 24 10 10 |

43.7 5.7 6.7 11.1 5.93 2.47 2.47 |

| Non-farm local services | Transportation Carpentry Tailoring Motor Mechanic Shoe making Rentals Barbing Hair plaiting BlacksmitButchery Soap making |

17 14 23 13 3 10 19 19 9 9 8 4 3 19 1 |

4.2 3.5 5.7 3.21 0.7 2.5 4.7 4.7 2.2 2.2 2.0 1.0 0.7 4.7 0.2 |

| Local trade | Petty Trading Sales of processed Agric. Products Food vending Water Trading | 67 50 13 2 9 |

17.0 12.3 3.2 0.5 2.2 |

| Local formal employment | Teaching Nursing LGA civil servant LGA night guard |

23 2 4 5 |

5.7 0.5 1.0 1.2 |

| Migratory wage services | Unskilled casual jobs | 9 | 2.2 |

| *Multiple responses | |||

The on-farm work is essentially working on personal farm in crop, livestock or fish farming. It is clearly observed in Table 3 that all the respondents were involved in at least one livelihood activity. Most of the respondents (84.4%) and (84%) were involved in arable and tree crop farming. Nearly half of the respondents (42.7%) were involved in livestock farming while only a few (11.6%) engaged in fish farming.

The result also reveals that nearly half of the respondents (49.4%) were involved in off- farm processing activities. Less than half of the respondents (44.1%) engaged in non- farm local services, such as carpentry (3.5%), shoe making (0.7%), motor repair (3.2%), tailoring (5.7%), barbing/hair plaiting (9.42%) among others.

This low level of the respondents‟ involvement in these activities, as shown in Table 3 might be due to the fact that some of these activities require skill, market availability, necessary rural infrastructural facilities and nearness to road and urban centers, with which rural dwellers are often constrained.

According to (Barrett CB et al., 2001) the farming on its own rarely provides a significant means of survival in rural areas of low income countries, including Nigeria. The inference that could also be drawn from this result is that the study area lacks enabling environment for sustainable non-farm livelihood activities and if this situation is not corrected it may impact negatively in the long run on livelihood diversification of rural households (Reardon T, 1997).

Table 4 shows that the levels of each of the livelihood assets (natural, physical, human, financial and social) were low. The aggregate level of livelihood assets in Table 4 also reveals that majority (56.3%) of the respondents in the study area had low access to livelihood assets while less than half of the total respondents (43.7%) had high access to livelihood assets.

| Livelihood asset | Level | Range | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural asset | High | 0-0.0913 | 394 | 97.3 |

| Low | 0.0914-6.00 | 11 | 2.7 | |

| Physical asset | High | 2.00-10.4197 | 237 | 58.5 |

| Low | 10.4198-28.00 | 168 | 41.5 | |

| Human asset | High | 0-7.4518 | 231 | 57 |

| Low | 7.4519-27.00 | 174 | 43 | |

| Financial asset | High | 0-1.3777 | 246 | 60.7 |

| Low | 1.3778-4.00 | 159 | 39.3 | |

| Social asset | High | 15-18.0493 | 262 | 64.7 |

| Low | 18.0494-20.00 | 143 | 35.3 |

This implies that respondents‟ livelihood asset is low and this may have adverse effect on their abilities to diversify into meaningful and profitable livelihood activities that can bring higher returns, thereby improving their well-being.

This corroborates who assert that livelihood assets are often hypothesized to affect the capacity of rural households to diversify their livelihoods.

Result from Table 4 reveals that rural households in the study area diversified their livelihoods for four main factors: sale only, household consumption, risks reduction, sale and consumption. The majority (72.4%) of the respondents diversified into arable crop farming for sale and consumption. More than a quarter (31.9%) as parts of off-farm activities for sales and consumption. The respondents were also involved in non-farm activities like carpentry (7.6%), transportation (2.5%) and barbing/hair plaiting (3.7%) for reduction of risk while a few respondents (1.24%) that involved in livestock production did so for consumption purposes.

The results further reveal that 49% of the respondents diversified into tree crop production for sales only. This may be a means of getting enough money in order to meet the need of the households.

Test of Analysis of variance in Table 5 shows that there was a significant difference in the respondents level of livelihood activities across the two LGAS selected for the study (F=2.891, p<0.05).

| Variable | DF | Mean Square | F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of livelihood Activities |

2 | 4.636 | 2.891 | 0.054 |

Result confirmed the differences with Kainji LGA as having the highest level of livelihood activities followed by Shiroro all in Niger State recorded the least level of livelihood activities. High level of livelihood assets in Kainji LGA might account for high level of livelihood activities recorded among respondents in Table 6 .

| Variable | States | MD | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of livelihood activities | Shiroro Kainji |

-0.309 -0.333 | 0.034 0.047 |

| MD=Mean Difference | |||

While least level of respondents‟ livelihood activities in shiroro LGA might be due to unfavorable rural environment which posed constraints like poor transportation system and lack of financial facilities that is very important for effective take-off in any livelihood activity.

Furthermore, result of comparison between the two LGAs which indicate not significant may be due to the fact that rural households in Nigeria are often characterized by similar features in terms of ability and accessibility to assets (Adediran D, 2008) that is very germane for effective engagement in various livelihood activities.

Conclusion

From empirical findings of this study, the following conclusions are drawn: Respondents were predominantly males, married and with low level of education. They were in their productive active years.

Respondents‟ primary occupation was farming with inheritance as their main source of land acquisition. Respondents had a mean age of 52.3 and mean household size of five which could be transformed into adequate support and experience of livelihood ability needed for effective livelihood sustainability. There is overall low income of respondents with average monthly income of N18851.85.

Social-economic characteristics such as primary occupation, primary income, length of stay, other income apart from income from primary occupation, frequency of visit to urban centre are important determinants of livelihood sustainability of rural households in Shiroro and Kainji LGAs of Niger State Nigeria.

Respondents‟ level of livelihood a bility was high, despite this; farming still engaged more people than non-farm activities.

Each of the financial, human, social, natural and physical livelihood assets contributes to the level of livelihood sustainability among the respondents. This notwithstanding, respondents‟ livelihood assets was low.

Many factors responsible for livelihood sustainability among rural households in the two LGAs of Niger State, Nigeria ranging from sales only, household consumption, reduction of risks to sales and consumption. Respondents diversified into different livelihoods (farm and non-farm) activities at both dry and wet season of the year.

Inadequate basic rural infrastructural facilities, livelihood assets, credit and marketing facilities were the severe constraints militating against livelihood diversification of rural households in the study area.

Abilities, assets and activities contributed to respondents‟ level of livelihood sustainability with ability contributing the highest, followed by assets while activities recorded the least contribution. In this study, it is concluded that respondents‟ level of livelihood sustainability in Shiroro and Kainji LGAs was low.

Recommendations

The following recommendations were made based on the findings of the study for the enhancement of sustainable rural livelihoods and improved standard of living in Shiroro and Kainji LGAs.

1. Government and NGOs should give more support to the development of formal and informal capacity building at the local level to enhance human assets of rural households and make them adopt more non- farm livelihoods. This could be achieved through provision of non-formal educational opportunities, primary education and establishment of technical and vocational schools which in addition to knowledge will provide employment and entrepreneurship.

2. Government should ensure that rural development programs are effectively implemented, monitored and evaluated. This will go a long way in ensuring conductive rural environment in terms of provision of adequate rural infrastructure that is very germane for livelihood sustainability.

3. Private investors and development partners should be encouraged to invest in rural areas. This will help tremendously in the fight against unemployment among rural households during off- season of agriculture.

4. Government, NGOs and other rural development stakeholders should try to make rural communities in Niger State conducive for development of human ability, livelihood assets and activities. This is because these three components and their interactions are important towards ensuring effective livelihood sustainability and improved well- being of rural households.

5. Enabling rural environment should also be provided by the government and NGOs in terms of establishment of micro financial institutions, access to other livelihood assets, reduction in vulnerability, training, provision of infrastructural facilities such as good roads, electricity, communication networks and farm inputs, marketing facilities, that will enable rural households to sustain their livelihoods at all seasons.

References

Abdulai A, CroleRees A (2001). Determinants of income diversification amongst rural households in Southern Mali. Food policy. 26(4):437-452. [Crossref], [Google scholar]Adediran D (2008). Effect of livelihood diversification on socio-economic status of rural dweller in Ogun State, Nigeria. Sc. Project, Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, University of Ibadan, Ibadan. 17-31.

Adekola G, Olajide OE (2007). Impact of government poverty alleviation programmes on the socio-economic status of youths in Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria. IFE PsychologIA: An International Journal. 15(2):124-131. [Crossref], [Google scholar]

Adeokun OA, Olanloye FA, Oladoja MA (2011). An overview of agricultural development in Nigeria Rural, Agricultural and Environmental Sociology in Nigeria, S.F Adedoyin(ed.), Ibadan and Ile-Ife, Andkolad Publishers Nigeria Limited. 192-193.

Aderinto A (2012). Effectiveness of stakeholders services on productivity of cassava farmers in southwest Nigeria. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

Babatunde RO, Qaim M (2009). Patterns of income diversification in rural Nigeria: determinants and impacts. Quarterly journal of international agriculture. Q J Int Agr. 48(4):305.

Babulo B, Muys B, Nega F, Tollens E, Nyssen J, Deckers J, Mathijs E (2008). Household livelihood strategies and forest dependence in the highlands of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Agricultural Systems. 98(2):147-155. [Crossref], [Google scholar]

Bakar TT (1999). Doing social research. Singapore: Mc Graw-Hill. 1-51.

Barrett CB, Reardon T, Webb P (2001). Nonfarm income diversification and household livelihood strategies in rural Africa: concepts, dynamics, and policy implications. Food policy. 26(4):315-331. [Crossref], [Google scholar]

Daneji MI (2011). Agricultural development intervention programmes in Nigeria (1960 to date): A review. Savannah Journal of Agriculture. Sav. J. Agric. 6(1):1-7. [Google scholar]

Davies S (1996). Adaptable livelihoods: coping with food insecurity in the Malian Sahel, London, Macmillan. 6-8.

Davies S, Hossain N (1997). Livelihood adaptation, public action and civil society: a review of the literature. [Google scholar]

Davis JR, Bezemer D (2003). Key emerging and conceptual issues in the development of the RNFE in developing countries and transition economies. [Crossref], [Google scholar]

De Janvry A (1981). The agrarian question and reformism in Latin America (No. HD1790. 5. Z8. D44 1981). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Crossref], [Google scholar]

Dercon S, Krishnan P (1996). Income portfolios in rural Ethiopia and Tanzania: choices and constraints. The Journal of Development Studies. JDS. 32(6):850-875. [Crossref], [Google scholar]

Devereux S (1993). Goats before ploughs: dilemmas of household response sequencing during food shortages. Ids Bulletin. 24(4):52-59. [Crossref], [Google scholar]

Devereux S (2001). Livelihood insecurity and social protection: a re‐emerging issue in rural development. Development policy review. 19(4):507-519. [Crossref], [Google scholar]

Reardon T (1997). Using evidence of household income diversification to inform study of the rural nonfarm labor market in Africa. World development. 25(5):735-747. [Crossref], [Google scholar]